Screened as part of NZIFF 2001

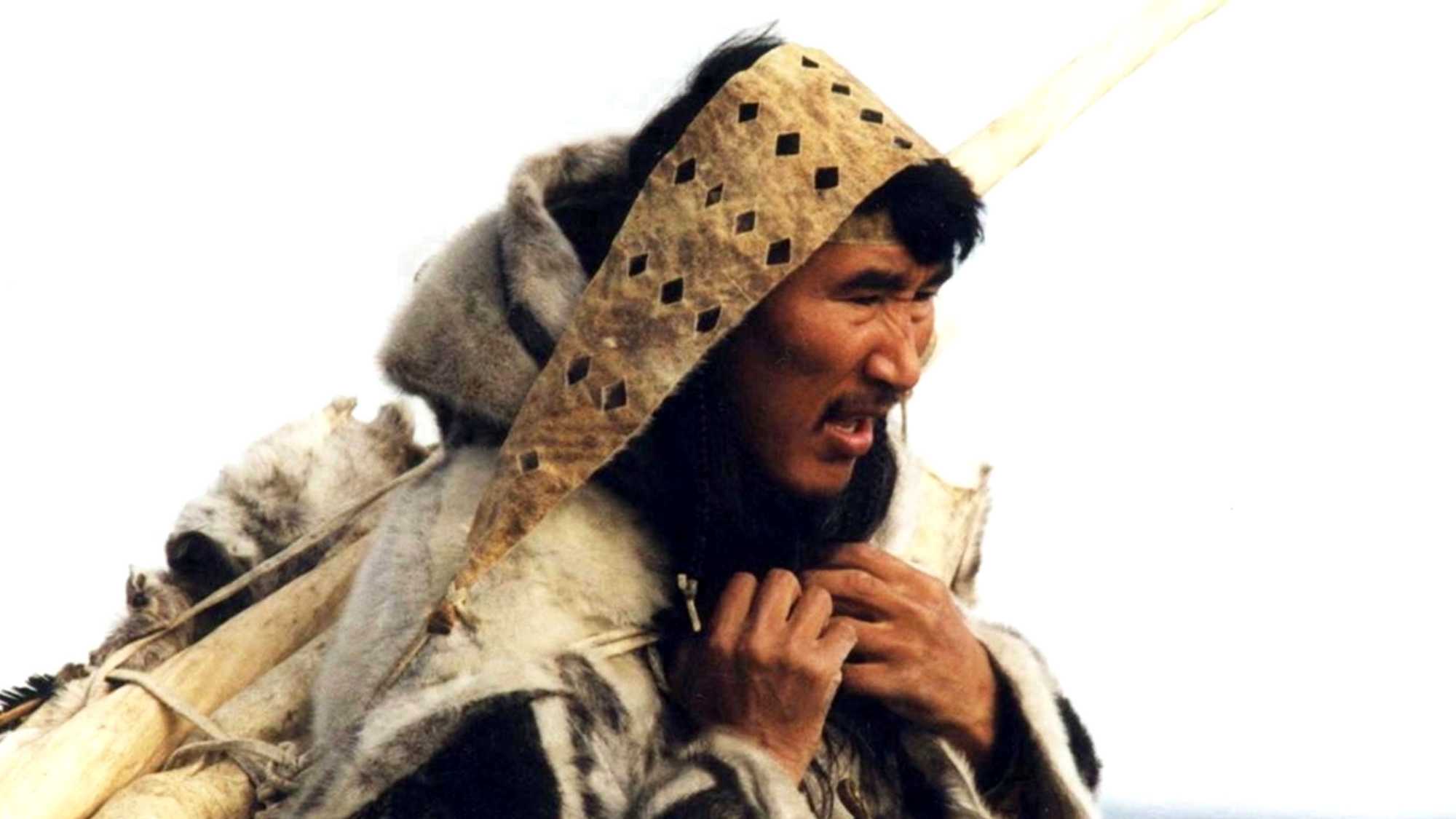

Atanarjuat, The Fast Runner 2001

‘We aren’t filmmakers – we’re a collection of artists who happen to use this medium to tell this story. Cannes is just a step along the way.’ So says Norman Cohn, the producer and cinematographer of Atanarjuat (The Fast Runner), the winner of the Caméra d’Or for Best First Feature for the film’s director, Zacharias Kunuk. But Kunuk and Cohn are by no means novices. Kunuk, a successful soapstone carver, joined fellow Inuit videomaker Paul Apak Angilirq (who wrote the screenplay for Atanarjuat before dying of cancer in 1998) and Cohn in the early 80s as part of the Inukshuk Project, which sought to capture Inuit ways of life on video ‘from the inside out’. Along with the Women’s Video Workshop, the Inukshuk Project was part of an explosion of videomaking in the unlikely location of Igloolik, Northwest Territories. The group’s most ambitious project was Nunavut (Our Land) (1994-95), a 13-part series that occupies a space somewhere between documentary and drama. The series concludes with the exceptional Quviasukvik (Happy Day), in which a large extended family celebrates Christmas Day in 1946 by giving thanks for a successful hunting season through song.

These videos are remarkable for their sense of community, especially in marking the bonds formed between individuals and family units through traditional rituals. Watching these unique works, one feels Kunuk would like to return to a time before Western influences began destroying his people’s traditional ways.

Atanarjuat continues the documenting of traditional Inuit lifestyle, but Kunuk takes it a step further, going further back to the Inuit’s very earliest legends. Four thousand years in the making, the legend of Atanarjuat is told to all Inuit children. It fascinated Kunuk from the first time he heard it, as he imagined what would it have been like to see a naked man, running across the barren ice, his feet bleeding, pursued by killers. Shakespearean in scope and dimension, the film tells the story of Atanarjuat (The Fast Runner) and his brother Amaqjuaq (The Strong One), and their rivalry with Oki and his brothers. In the film’s opening scenes, Oki’s father usurps power by murdering his own father with the help of a stranger, and the evil falls to the next generation. After Atanarjuat (Natar Ungalaaq) beats Oki (Peter-Henry Arnatsiaq) in a contest for the hand of Atuat collapses (Sylvia Ivalu) – in which each contestant punches the other in the temple until one! – Oki plans revenge. Arranging for his sister Puja to seduce Atanarjuat and become his second wife, Oki and his brothers kill Amaqjuaq and send Atanarjuat on his naked run. The rest of the film concerns Atanarjuat’s revenge upon Oki, which, when it comes, takes a surprising form.

Speeding by with ease, the labyrinthine plot is surprisingly easy to follow. Throughout, Kunuk presents the mythical story in realistic terms, depicting the day-to-day alongside more dramatic events. For instance, when the brothers are ambushed, we see the care with which Puja lays out their furs to dry, while the brothers sleep, oblivious to her true intentions. Similarly, when a family rescues Atanarjuat, they are collecting bird’s eggs on the tundra. To hide Atanarjuat, they bury him in the pile of seaweed, which forms the fuel for their fire. The scene following reveals Kunuk as a sly humorist. Oki, arriving at the camp looking for Atanarjuat, relieves himself on the seaweed pile, unaware that his prey is hiding beneath it. After Oki leaves, Atanarjuat emerges to exclaim: ‘He pissed right in my face!’ Such moments humanize the characters, giving the sense that they are real people to whom extraordinary events happen rather than larger than life but lifeless mythological beings.

Another remarkable feature of the film, and of Kunuk’s work in general, is the attention paid to the role of women in the society. It is Atuat who pursues Atanarjuat, against the wishes of her father, and it is Oki’s grandmother Panikpak who supports their marriage and cares for Atuat when she is ostracized by the tribe following Atanarjuat’s disappearance. It is also the grandmother who pronounces the tough but fair judgement on Oki and his clan at the end of the film. Ultimately the message of the film – and the legend – is one of self-examination and forgiveness, but also of evil being challenged and overcome through the strength of the collective. As in the earlier video documents, Atanarjuat manages to capture a marvellous sense of a very complex community at work. It reveals Kunuk to be a masterful observer of human interaction, and a filmmaker worth watching. — Bill Evans, Cinema Scope, Spring 2001