Screened as part of NZIFF 2002

Chop Suey 2000

‘We sometimes photograph the things we can never be,’ says filmmaker Bruce Weber, while his camera puts us alongside shirtless young hunks exercising on a construction site. ‘And the men we can never have,’ one might add, as Weber goes on to confess that he was always too embarrassed to undress in front of other guys himself. His camera then follows these impossibly nonchalant athlete/models into the shower.

When Weber undressed and photographed the wholesome all-American boy to sell Calvin Klein’s underwear, he, and the fashion editors who published him, shifted the way men are seen in popular culture. Hearing him own up to sharing the sense of exclusion – call it desire – that his work instills in gay men and straight, is one of many frissons that quicken his woundingly beauty-filled film.

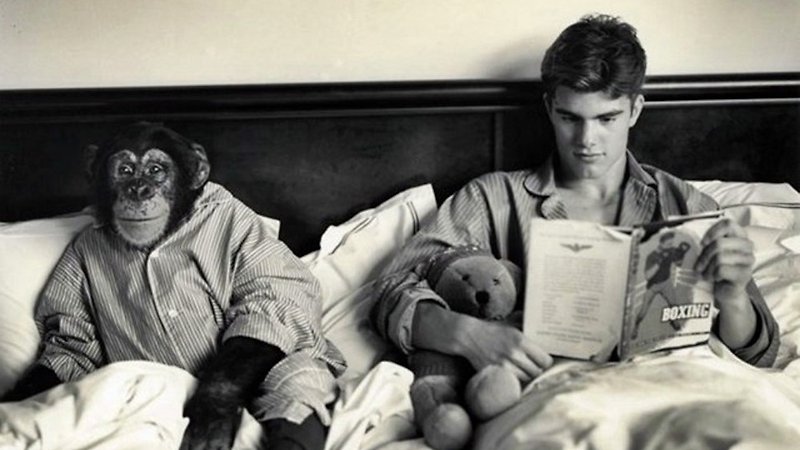

Chop Suey is a scrapbook of Weber’s obsessions, ostensibly addressed to the unattainable young man of the moment, Peter Johnson, a high-school wrestler whom Weber discovered in Iowa and has been photographing all over America ever since.

Though Weber tells the story of Sinatra’s eviction of Phil Stern, whose photographs of the Rat Pack had defined their raffish allure, and though he reminds himself that ‘movie stars are not your friends’, he openly craves family status with the wild and beautiful. His first assignment, Jan Michael Vincent, was a real buddy, he assures us, before intercutting buddy’s full-frontal walk-to-camera from Buster and Billie with footage of Robert Mitchum recording Sleepy Time Down South! This assertion of kinship through fanboy-montage is as intensely lyrical as it is nuttily idiosyncratic – and as self-defining as a teenager’s bedroom wall of celebrity centrefolds. It also acknowledges, tacitly, the self-taunting that gives Weber’s elegant flow of ravishments the added glamour of a dangerous undertow. What man ever had Robert Mitchum?

Other celebrities who make striking appearances include a Brazilian jujitsu champ; Christian Fletcher, an ex-junkie punk surfer; the explorer Wilfred Thesiger; Vogue editor Diana Vreeland and, above all, Frances Faye, the butchest of girl singers whose belting renditions of jazz standards help drive the film from one obsession to the next. An out lesbian who began her shows with the cry ‘Gay,gay, gay. Is there any other way?’ Faye is recalled in clips, photos and in conversation with her surviving partner, Teri Shepherd.

But the obsession that binds Chop Suey is photography; with the relationships between artist and model, admirer and admired, memory and memento. You have never seen photographs – Weber’s own and many more – depicted so lovingly in a movie. The photos themselves are objects of desire. They’re as abundant here as leaves in a forest, but the camera brushes each one with a kiss and maybe, if we’re lucky, a story about its photographer and their relationship to the men or women in the photographs. ‘It’s all about pussy,’ David Bailey told Weber. And we hear Edward Stieglitz warning that any man who wanted his wife photographed by Stieglitz was taking a terrible risk. Again and again Weber returns to the idea of photography as a means of fashioning something beautiful and permanent out of sexual desire.

That photography might be his only response to sexual desire is implied in his reticence on the subject of his own experience – and in the sweet innocent chumminess he ascribes to his dalliances with such notorious hedonists as, well, Jan Michael Vincent and Robert Mitchum. He talks about persuading Peter Johnson to get naked like it’s a fun new adventure sport he ought to try. It has often been suggested that Weber’s personal coyness is a trade-off and it certainly helps equip him for a peculiarly American form of success. (He’s photographed Bill Clinton with boy scouts.) But Chop Suey resonates with the possibility that the thrill of desire that his work induces in the viewer is fuelled by Weber’s own self-denial. The mere existence of this meticulously crafted film, which cannot possibly have been made in the hope of turning a profit, tells us something significant about where he finds his pleasure.

Staying out of sight, he offers himself to us as a splendid collection of deluxe appropriations: the curl of Diana Vreeland’s lip, the smoke of Mitchum’s cigarette, the lope of a big friendly dog and the momentary emergence in the developing tray of a high-school athlete’s cock, undressed at last. Chop Suey is a piquant show-and-tell, a sophisticate’s tour that delves surprisingly deep into the hurting heart of advertising. In its jazzy, dynamic, highly individual fashion Chop Suey is as informative about our image-buffeted lives as any film on this year’s programme. — BG