83 minutes

Screened as part of NZIFF 2002

KINETICA-2: A Centennial Tribute to Oskar Fischinger

Oskar Fischinger was not only one of cinema’s greatest technological visionaries, he was one of its greatest lyrical artists as well. His primary theme was the abstract visual representation of music, and in the course of exploring this theme throughout his career he created some of the most precise and beautiful marriages of sound and image the medium has ever produced. Fischinger was so dedicated to this mission that, in the 1920s, he would not even let the non-existence of synchronised sound film deter him from realising his dream of illustrating with motion his favourite pieces of music. While the influence of Fischinger’s animation on the work of Len Lye, Norman McLaren and their followers is direct and obvious, periodic collaborators such as Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Fritz Lang, Leopold Stokowski, Orson Welles and John Cage carried his ideas even further afield.

Fischinger was born in Geinhausen, Germany in 1900. He trained as both a musician and an engineer, but in 1921 he realised that his vocation lay somewhere in between when he attended, and was transfigured by, the first public screening of an abstract film, Walther Ruttmann’s Opus 1.

His eventful early career in Germany saw him devise a mechanism for generating abstract animation out of slabs of marbled wax (the shimmering finished product gives viewers some idea of what it might be like to live inside a lava lamp), create expertly synchronised music videos without the benefit of sound film, generate some of the first electronic music (Licht Musik) by drawing his own optical soundtrack onto film, and assist in the development of one of the earliest and best colour processes, Gasparcolor.

(The early colour films featured in this programme will sear your retinae with their brightness and clarity.) Along the way, he synthesized a brand-new aesthetic of animation from elements of expressionism, futurism, cubism and arts nouveau and deco while looking forward to pop art, op art, psychedelia, minimalism and action painting.

Fischinger’s career in Europe was effectively ended when he was branded a ‘degenerate’ artist by the Nazi regime. He moved to Hollywood and was soon in demand. Although everyone acknowledged his talent, nobody in Hollywood really knew what to do with Oskar. Allegretto was completed for The Big Broadcast of 1937, but left out of the film when the artist refused to sanction its reduction to black-and-white. His tenure at MGM resulted in only one film, An Optical Poem, before they decided that churning out Tom and Jerry shorts would be a more lucrative use of their resources. A proposed collaboration with Orson Welles stalled amidst the wreckage of Welles’ South American project. The animator’s most prestigious commission was one to design the opening segment of Disney’s aspirational show-pony Fantasia. He left in frustration long before the sequence was completed, and the finished Toccata and Fugue was a banal, bastardised version of Fischinger’s original vision. And yet, even in its banality, the segment showed up the imaginative paucity of much of the rest of the film.

Fischinger in Hollywood became yet another unemployable genius-about-town, continuing to experiment, but turning increasingly to oil painting and relying for his film funding on private commissions such as the one which resulted in his astonishing Motion Painting No 1. When that final masterpiece failed to please its patroness, the Guggenheim’s Hilla Rebay, Fischinger’s career in film effectively ground to a halt, and his creativity was redirected to abstract painting. He died in 1967 after a long illness.

This programme of films, curated by the iotaCenter, is but a selection from an extraordinarily rich, extraordinarily intense body of work. (The title is supplied by the iotaCenter too. Don’t go looking for a KINETICA-1 on our programme.) It begins with a brief introductory video documentary and works chronologically through Fischinger’s career, presenting the films in the iotaCenter’s beautiful 35mm prints, culminating with his magisterial Motion Painting. — Andrew Langridge

Oskar Fischinger: The Creative Spirit 2000

Documentary on Fischinger, featuring interviews with his biographer, wife and daughter.

R-1: Ein Formspiel 1927

A film Fischinger compiled from fragments of many of his earliest experiments.

Study No 1 1929

Study No 2 1930

Fischinger’s superb series of film studies, brief visual accompaniments to pieces of classical or contemporary music, were created with the simplest of means. Oskar drew his figures in charcoal on paper. These were filmed, then that film was used as a negative, resulting in Fischinger’s signature look: gleaming white shapes gliding across an inky background. The earliest of these visual music experiments took the form of silent film ingeniously synchronised to phonograph records.

Study No 6 1930

Flying objects illustrate Los Verderones, a fandango by Jacinto Guerrero. One of Fischinger’s finest studies, this film was withdrawn from circulation when Guerrero demanded a vast fee for the use of his music.

Liebesspiel 1931

Music without sound. ‘Liebesspiel has a classical simplicity unique among Fischinger’s work, with a clear sense of phrasing, development and beautiful spatial construction which make it his most perfect transcreation in a visual format of the basic musical ideas of melody and harmonies as they might occur in a song or lyrical air.’ — William Moritz, Film Culture, 1974

Study No 9 1931

Hungarian Dance No. 6 by Brahms gets the Fischinger treatment: being broken down into visual Morse code and played back to itself. This film, on which Oskar’s brother Hans assisted, was his first collaborative animation.

Study No 11A 1934

The second of two undulating studies synchronised to the Minuet from Mozart’s Eine Kleine Nachtmusik. This version introduces colour to the distinctive monochrome world of the Studies for the first and only time.

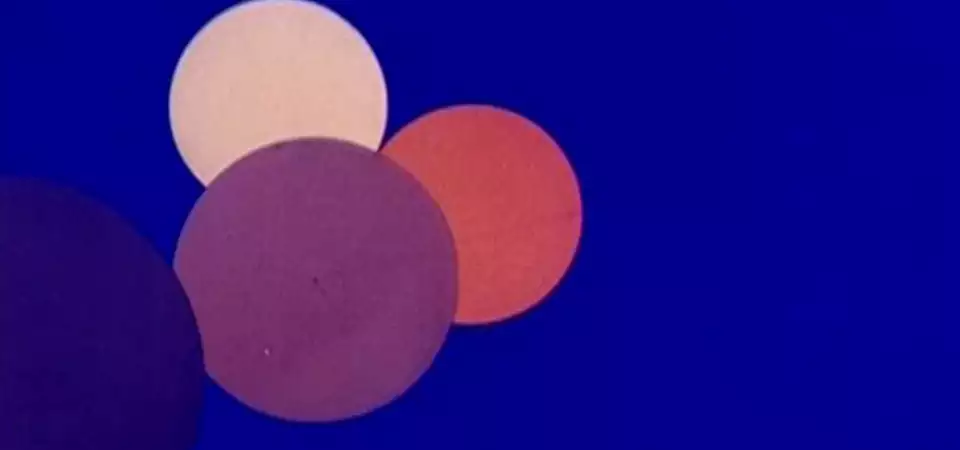

Kreise 1933

Globes, mesmeric spirals and the constant surprise of Gasparcolor, a three-colour film process the animator developed with Béla Gaspar. The hyper-real primaries of Fischinger’s first colour film were ideally suited to the clarity and intensity of the process. Music by Grieg and Wagner.

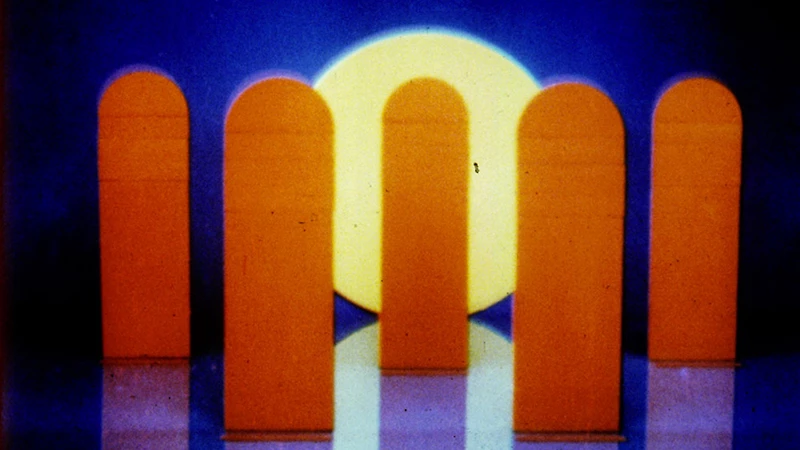

Composition In Blue 1935

This is an example of Fischinger’s object animation, another field in which he excelled. This abstract, colourful (very blue, very red) choreography of 3D geometric forms is closely aligned to his memorable series of cinema ads for Muratti (think Busby Berkeley with cigarettes) and shows the same precision of synchronisation that lends his Studies such visceral excitement.

Allegretto, Early Version 1936

This utterly modern op-art interlude was intended for a Paramount feature, but when the studio bosses insisted that Fischinger would have to lose the stunning colour (what were they thinking?!), Oskar walked. He subsequently bought back the rights to the film and continued to work on it (see below).

Paragretto 1936

A spin-off of Allegretto (see above).

Allegretto, Late Version 1943

A revision of Fischinger’s ill-fated Paramount project (see above), facilitated by Guggenheim funds.

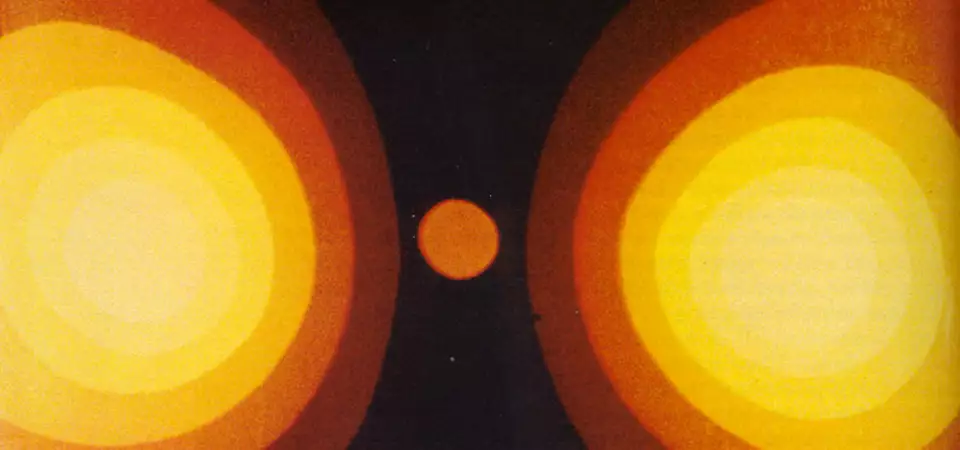

An Optical Poem 1937

Scored to Liszt’s second Hungarian Rhapsody, this dazzling film was the sole product of the filmmaker’s brief stint at MGM. One of Fischinger’s assistants in arranging the tiny pieces of paper that dance around the screen was a young John Cage, who was much taken with his boss’s theories of electronic music.

American March 1941

Eye-popping colour treatment of The Stars and Stripes Forever.

Radio Dynamics 1942

This deliberately silent, meditative film was produced privately in the calm after one too many studio storms. "A silent animation in which the virtuosity of form and colour is enough to evoke imaginary mental music in the viewer’s unconscious." — Philippe Langlois

Motion Painting No 1 1947

Fischinger’s visual accompaniment to Bach’s third Brandenburg Concerto is one of the most profoundly satisfying fusions of sound and image you’re likely to see. Oskar’s counterpoint is never obvious (but then nor was Johann’s), yet the gentle evolution of the pointillistic image matches the soundtrack crescendo for crescendo. To create this visual alchemy, the animator painstakingly applied oil-paint to plexiglass, capturing the changing patterns of paint a frame at a time over six months.

When the first sheet became unworkably paint-logged, Fischinger superimposed a second and continued painting, obliterating what went before. The abstract forms change incrementally but completely, climaxing with dynamic washes of colour. In this way, the artist manages to match the splashy passion of Jackson Pollock with the formal rigour of J.S. Bach, and the resulting tension is something to behold.