The Auckland Philharmonia performs Edmund Meisel’s score for Sergei Eisenstein’s, Battleship Potemkin, conducted by Helmut Imig. Presented in association with The New Zealand Film Archive.

The Auckland Philharmonia performs Edmund Meisel’s score for Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, conducted by Helmut Imig. Presented in association with The New Zealand Film Archive.

Screened as part of NZIFF 2005

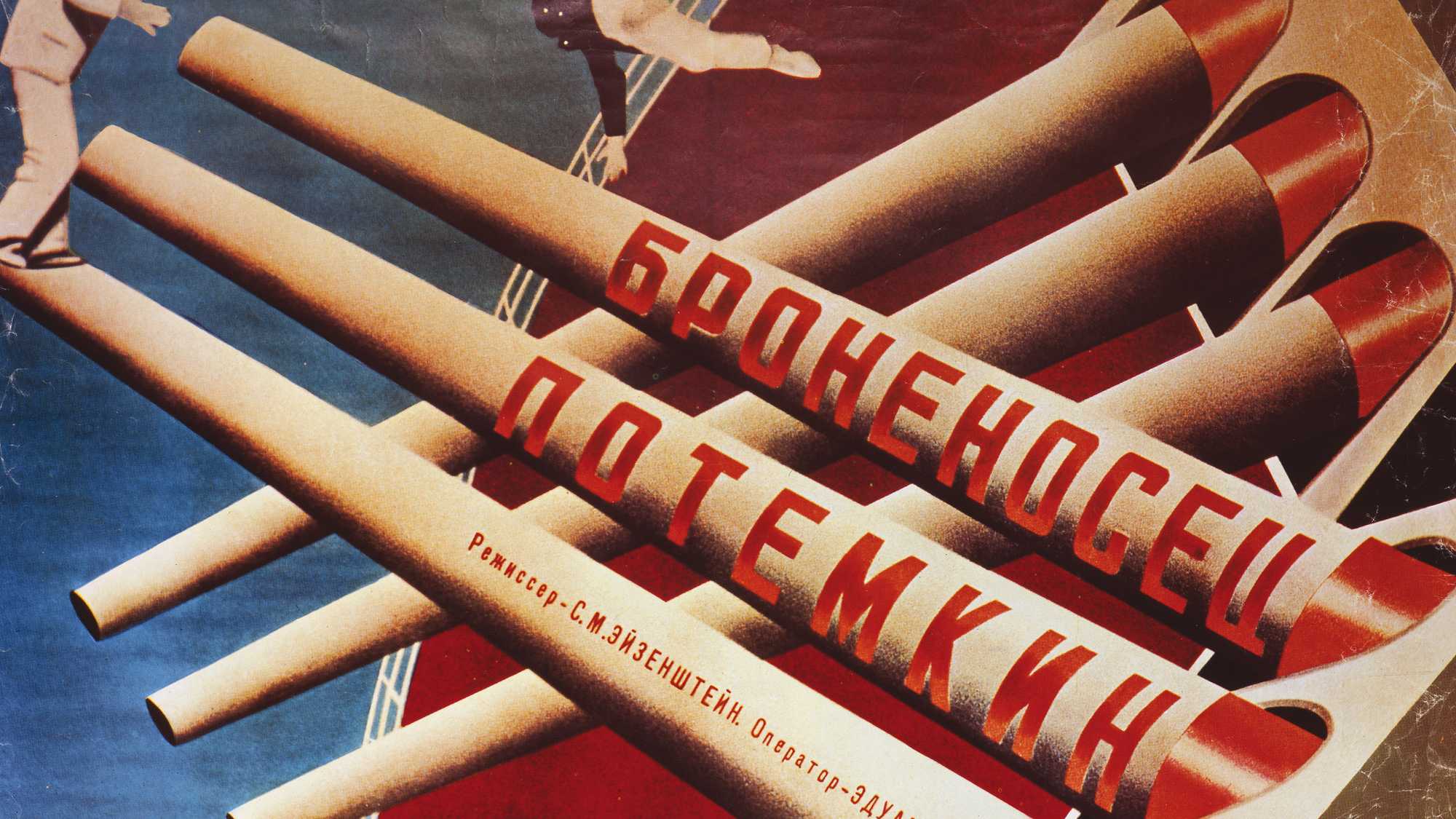

Battleship Potemkin 1925

Bronenosets Potyomkin

Perennially famous but rarely seen these days, Battleship Potemkin has consistently ranked amongst the greatest films of all time in British film monthly Sight and Sound’s ten-yearly surveys of international critics and filmmakers. In 2002 it slipped to number seven, between Kubrick’s 2001 and Fellini’s 8½. Not bad for the 80-year-old tour de force of Soviet propaganda. Commissioned to arouse revolutionary ardour, the film glorifies those who died when a 1905 mutiny onboard the Potemkin was brutally quashed by the Tsarist navy.

Ironically, it was in Germany, not the USSR, that Battleship Potemkin became an enormous hit. In 1925 the German distributor commissioned the Austrian-born Edmund Meisel to write a score for theatre orchestra. By the time Eisenstein turned up in Berlin, Meisel had reached the last reel, in which the battleship, with the mutinous sailors on board, goes out to confront the navy, tension mounting as the ships approach one another. Eisenstein’s advice to the composer was: “the music for this reel should be rhythm, rhythm and, before all else, rhythm”.

Long considered lost, Meisel’s brilliant, pulsating score has been rediscovered and restored by German composer/conductor Helmut Imig. Its première at the 2005 Berlin Film Festival in February was a sensation. We’re delighted that Helmut Imig has accepted our invitation to conduct the Auckland Philharmonia in the first performance outside Europe of this astounding score.

In a Live Cinema presentation of a handsome new print from the Bundesfilmarchiv in Berlin, restored to its fullest known length with the assistance of the British Film Institute, it becomes clear why the movie has so often been considered dangerous. It’s been banned at various times in the United States, France and the UK, and in the Soviet Union too when mutiny was no longer considered glorious. There are those who believe the Film Society movement sprang into existence simply to disseminate this suppressed film.

“It’s amazing… it keeps its freshness and its excitement, even if you resist its cartoon message. Perhaps no other movie has ever had such graphic strength in its images… The Odessa Steps sequence, the most celebrated single sequence in film history, has been imitated in one way or another in countless television news programs and movies with crowd scenes; it has also been parodied endlessly. And yet the power of the original is undiminished.” — Pauline Kael

“[Live] the film did have headlong momentum, thrilling juxtapositions and genuine power to move – most especially during the Odessa Steps sequence, which had some viewers gasping out loud.” — Roger Ebert

Helmut Imig. Born in Bonn, Helmut Imig studied piano and conducting at the Musikhochschule in Cologne, and went on to study musicology at the University of Bonn. In 1964 he won a scholarship to continue his studies in Paris with the pianist Annie D’Arco and the conductor Pierre Dervaux; and also took masterclasses with Franco Ferrara in Venice and Igor Markevitch in Madrid. He now regularly conducts orchestras in Cologne, Bonn, Lugano and Hamburg, specialising in avant-garde music, opera and music for silent films – for which he has resurrected many original scores by Saint-Saëns, Mascagni, Hindemith and Shostakovich.