The death of a boxer in 1962 is the focus for an intelligent, many-faceted consideration of brutality, machismo and sport. “An amazing story” — NY Times

Screened as part of NZIFF 2005

Ring of Fire: The Emile Griffith Story 2004

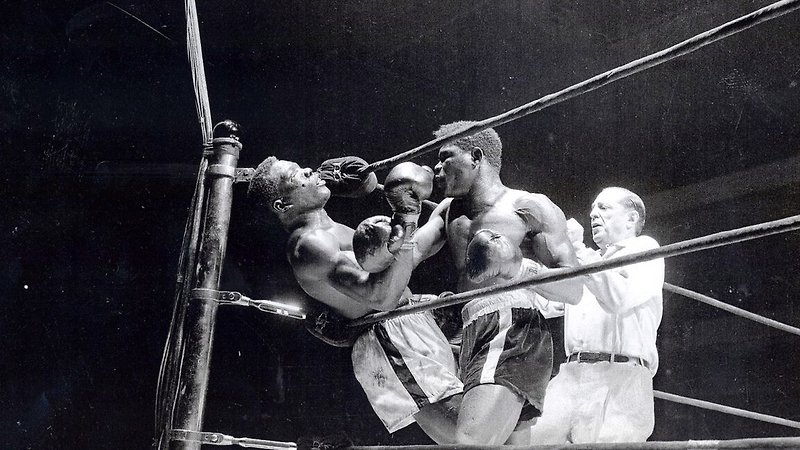

In 1962 the sport of boxing suffered an enormous setback to mainstream acceptability, when Benny ‘Kid’ Paret died after being pummelled by six-time welterweight champion Emile Griffith at Madison Square Garden, on live network televison. Dan Klores and Ron Berger delve deeply into this event, drawing a wealth of testimony and analysis from a gallery of veteran New York boxing identities and commentators. We hear too from Griffith himself and Paret’s wife and son. A gentle giant plucked from obscurity in a hat factory, Griffith seems to have been motivated into the ring by the desire to please his trainer and manager, and then stayed to enjoy the rewards of being champ. Though he once married and assures the filmmakers he’s nobody’s faggot, there’s plenty to suggest he’s gay. Legend has it that the fatal assault was motivated by Paret’s homophobic taunts. Klores and Berger’s intelligent consideration of brutality and sport settles for no such simple answer to the question: ‘Who or what is really to blame for Paret’s death?’ — BG

"Ring of Fire could easily have made Griffith, who has had short term memory problems since a 1992 street attack that may have been a gay-bashing, look like a pathetic figure or a kind of noble dimwit. It does neither. Instead it lets others tell his story and the story of his time and place, the New York boxing world of the late 50s and early 60s, and then it lets him talk. We see the unshakable sadness he’s carried for four decades since Paret’s death, but also the pride he takes in his achievements. Though it’s often said of Griffith that he was never the same fighter after Paret’s death, he was either the welter or middleweight champ for most of the next six years, and he fought for the middleweight title as late as 1973. And we see his playfulness and humor, the sweet side that’s made him so well liked throughout his life, that made him so poorly suited for his brutal calling. As a teenager new to America he got a job in a garment center hat factory. One day he asked the boss if he could take his shirt off. The boss, Howard Albert, took one look at Griffith’s chiselled upper body, marched him down to Gleason’s Gym to introduce him to Clancy, and became his manager. ‘So that was my trouble right there,’ Griffith says wryly, ‘taking my shirt off.’" — King Kaufman, www.salon.com