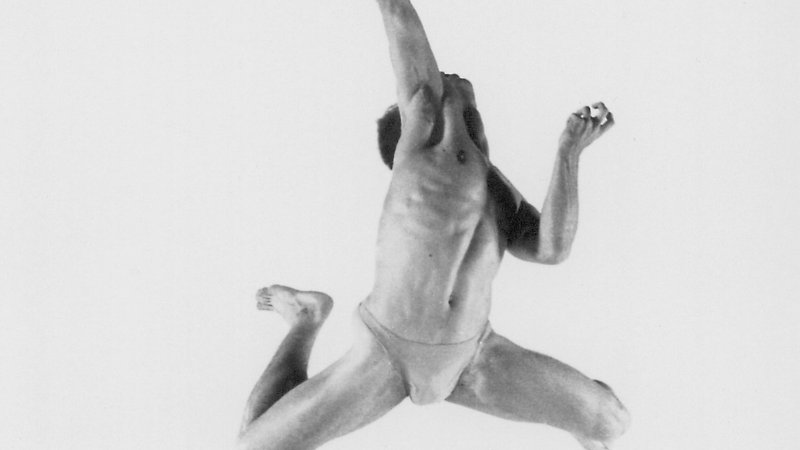

I need to make things to feel that I can cope with whatever reality is. For me, dancing, performing for people, is the ultimate mystery and the ultimate joy.

Screened as part of NZIFF 2003

Haunting Douglas 2003

Douglas Wright, New Zealand’s prodigious contemporary dance choreographer, has demonstrated his customary instinctive intelligence in agreeing to work with Leanne Pooley, an accomplished filmmaker who knew little about him or about contemporary dance. Struck by his intensity in a newspaper photograph and amazed by the pungency of what he said, she wanted to know more and approached him about making a documentary. There’s a point in the resulting film where he fixes her camera with eyes like darts, and declares that putting his ‘pain or whatever’ on display is the price he’s obliged to pay in order to get his work in front of people again. Penguin Books will soon publish Wright’s ‘autobiographical fiction’, so his avowed aversion to personal revelation should not be taken too literally, but there’s no questioning his cynicism about the dynamics of arts celebrity. With appealing modesty and good humour, Pooley includes her professional relationship with Wright within the frame of the portrait. His reproaches and his commentary on the process become an integral feature of this engagement with a most remarkable man.

She had indeed already agreed to allow Wright approval of her selection of the dance excerpts that stud the film. Watching these intstances of Wright’s extraordinary work with Limbs, Paul Taylor, DV8 Physical Theatre, the Royal New Zealand Ballet and with his own companies is an intensely pleasureable experience. The fleeting passage of so many startling moments from works of such condensed brilliance as Wright has given us, exacerbates the craving induced by any truly gripping choreography, to rewind time – or otherwise extend it. It’s hard to imagine an audience who’d watch this film and not emerge wanting to experience these works in their fullness. The preservation and accessibility of every moving picture of Douglas Wright’s choreography should be national cultural priorities.

Tracing the often punishing life from which this work has sprung, Pooley draws on Wrights own accounts as vividly enunciated in the forthcoming book, while friends and colleagues, here, in New York and in London, provide anecdotal testimony to his singularity and their enduring amazement. Though she remonstrates with him when he’s devastated by a single bad review in a welter of good ones, Pooley clearly apprehends Wright’s ‘pain or whatever’, his overwhelming sense that he has failed to reach us. He expresses himself in bitingly enunciated paradoxes, reaching us again and again, now that his body refuses to dance, with the vital, lucid artistry of his words. I can think of no more appreciative, perceptive or powerful documentary portrait of an artist in New Zealand than this. — BG