Screened as part of NZIFF 2003

Tape 2001

In his previous films Richard Linklater has expressed an almost obsessive attention to the classical unities. Slacker, Dazed and Confused, Before Sunrise and SubUrbia all took place over a day and a night in a single locality. Tape takes that dramatic preoccupation to its logical conclusion: three characters, in a single motel room, in real time.

With a chamber piece of such extreme minimalism, the key is to get the script right, get the actors right, and stand back. In these surroundings, that final step would have been all but unthinkable before the advent of digital video, and Linklater’s claustrophobic drama serves as an exemplary DV feature: deceptively loose and uncomfortably intimate. And the other requirements are equally satisfied. The director has found a clever Chinese-box narrative in Stephen Belber’s one-act play and elicits tough performances from his stars.

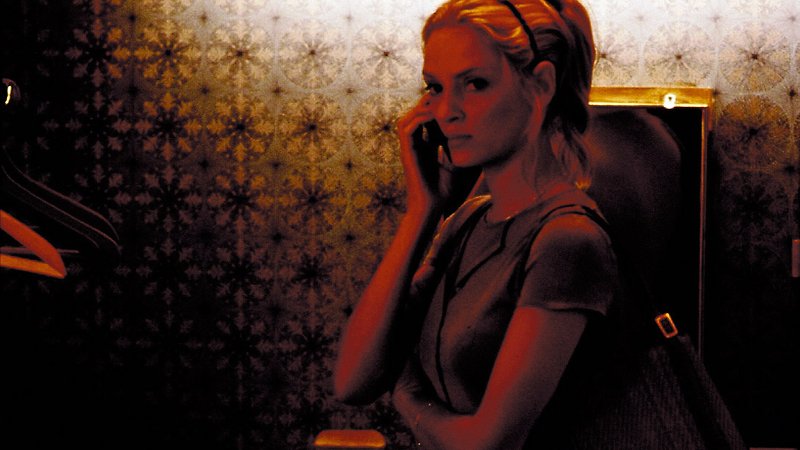

Ethan Hawke is awesomely unpleasant as the manipulative Vince, back in town to catch the local film festival première of an earnest documentary by his old friend, John (an efficiently slippery Robert Sean Leonard). As long-stagnating jealousies and petty resentments bubble to the surface, and upwardly mobile John prepares to bestow precious life lessons on no-hoper Vince, their talk circles dangerously around to Amy, a girl with whom they had both been involved in high school. Whose girl was she really, and when does being ‘a little rough’ shade into date rape? As Amy, Uma Thurman is ferociously self-possessed, and when she enters the film in its final third she messes mercilessly with the power plays that have been constructed around the chimerical incident, leaving the characters and the audience scrabbling for answers.

Although Linklater’s camera is surprisingly resourceful given the spatial constraints (imaginative angles, arch whip-pans during ping-pong dialogues), Tape does start out wordy and actorish. Once you realise that this story is one that is concerned, almost at the molecular level, with acting and with words, and that there’s an alibi for the staginess – this encounter has indeed been staged – the story has you hooked, and it’s easier to enjoy watching the characters squirm, and these Hollywood actors getting their teeth into roles of real substance. — Andrew Langridge